I remember seeing Bob Dylan live in around 1978 in Perth Western Australia. I have to confess, in regards to Bob, I was more admirer-from-afar than fan, though I do remember as a pimply 13 year old, hanging out with a friend who had a few LP’s, and lying on the carpet in front of his parent’s gramophone player, listening over and over to Ballad of a Thin Man.

I went to see the Dylan concert because someone I knew was playing in the support band, and scored me some free tickets, so I wasn’t going to say no. I can’t remember anything much about what they played that night, though they did cover most of the Dylan classics, and I remember talking to his drummer afterwards, the remarkable Ian Wallace, who more obsessional fans of early British Prog-Rock will recognise as the drummer on a couple of early King Crimson LP’s. I was intrigued as to why a prog-rock English drummer was playing with Dylan, but well, hard to imagine anyone finding too many reasons not to.

While my recollection of the song details is hazy, I do however have two clear recollections of the concert itself: the first is that Dylan played a black and white Strat, and the second is that as a guitarist, he knew exactly what he was doing. I was blown away. He didn’t do anything flashy or tricksy, or in fact anything that you wouldn’t hear if you hung round the average guitar shop on a Saturday afternoon. But, he knew exactly where to do what he did, and he knew exactly what each song needed, little as it may have been. I came away a convert, not so much of Dylan the lyricist (yes, we knew that already), or of Dylan the songwriter (that too), but of Dylan the musician.

So, to Like A Rolling Stone. One of the greatest pop/rock/whatever songs of all time. Rolling Stone magazine have it as THE greatest song of all time, and (I’m quoting from Wikipedia here), it’s “one of the most influential compositions in post-war popular music”. Great lyrics, a great melody, a great studio band, some great playing and a really great vocal performance. For most of us, even a couple of those would be enough. Maybe for Bob too. But what lifts the song into another class altogether, is that behind all that greatness is some remarkable work around form and structure, i.e., the way all those great ideas are put together.

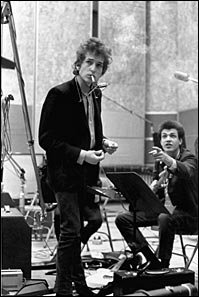

The story of the recording of Like a Rolling Stone adds to the legend of the song itself. How Al Cooper had been invited along to the session, thinking he’d be playing guitar. But when 22 year old Mike Bloomfield walked in, carrying a Telecaster without a case and covered in snow, he retreated to the control room. How Al Cooper (again) snuck back into the studio to take up position on the vacant Hammond Organ, and started tentatively playing along, but was so unsure of what was going on, he waited till beat 2 of each bar to play so he could hear what chords the other musicians were changing to. At least until the song hits the bridge because if you had to gamble your life, (or a credit on a Bob Dylan album), on a key change, you’d be betting on a shift to the subdominant (the fourth) for the bridge. Which is what happens, and where Al and his Hammond attacks on the downbeat. And then, how the producer, Tom Wilson wanted the organ mixed down or cut because Al Cooper wasn’t even a keyboard player, but Bob, with ever the ear for what was right, insisted that not only was the organ kept, but it was turned up, bringing to the fore one of the most iconic keyboard parts in rock history. People have written books around these sessions, and there was even an evening-length play mounted in Paris last year built around the recording of Like A Rolling Stone.

So, the song, the song. Or, should I say, THE song. We have a verse. We have a bridge. We have a chorus. Nothing radical, but then even radical songs have been written around verse, bridge, chorus. The verse is in C major, with an ascending chord pattern that ends up on a held G for the last 2 bars of the 4 bar cycle. The bridge, as Al Kooper fortuitously guessed, is up a fourth in F, and in contrast with the movement of the verse, it opens out. The two-to-a-bar changes of the verse slow right down to square one-to-a-bar held chords. But then these pick up again in the lead into the chorus, where a run-down to the tonic mirrors the run up from the tonic in the verse. It’s not just Schoenberg and Webern who were handy with retrograde. This is followed by 4 bars of held chords, first F and then, naturally enough, G, the dominant.

That’s a lot of harmonic content already, and it isn’t all that surprising that it takes us 20 bars to work through it all. It’s equally not surprising that when we hit the chorus, things simplify right down and straighten out to a simple 2 bar repeated pattern of C F G. In other words, we have one of the greatest songwriters of all time, working on one his greatest songs, and he gives us no more or less than a kid in his/her bedroom knocking together his/her first tune: C. F. G.

In spite of how blindingly obvious the choice in the chorus is, there’s some serious work going on in the way the chord changes are structured:

In the verse, the 4 bar pattern alternates 2 to a bar on the run-up, with a chord held over the subsequent 2 bars. The bridge then shifts the tonal centre – as all Bridges tend to do, or even need to do or else they wouldn’t be Bridges, they’d simply be variations of Verses – before it all comes back together in the tonic C in the chorus.

The bridge also reverses the harmonic structure of the verse, not only in the direction of the movement, but in the harmonic rhythm, swapping more rapid changes moving to a held chord, with a held chord moving to more rapid changes, albeit over a longer period. Following that, Dylan uses another classic bridge device by simply sitting on the subdominant and then dominant for 4 long bars, 2 bars each.

The Chorus dumps all this shifting of harmonic rhythm and form, to give us that simple repetition of C F G, a kind of double-time version of what happens in the Verse, squeezing into 2 bars what the verse takes 4 bars to work through. Which, once again, is a classic chorus device: speed up the chord changes and/or shorten the cycle. So, while the chord changes themselves are no more rapid than anywhere else in the song, by halving the length of the cycle to 2 bars as opposed to the 4+ bars we see throughout the rest of the song, we get an increased momentum that gives the chorus drive and energy. The verse sits, the bridge floats, the chorus lifts and takes off, and everyone gets up out of their seats.

But Bob wasn’t done there. In fact, he’d only just started. Because all this work with shifting and structuring chords is, after all, only the framework to hang a melody on. And it’s what he does with the melody that takes the song into another league altogether.

Verse melody: nothing special in itself. To start the singing on the downbeat is a bit risky in some ways as it’s very square and the risk is that it’ll all be a bit flat. Most verse melodies start behind the beat, often around beat 2, with gives you that kind of off-beat kick. Getting back to Al Kooper, it’s his beat 2 organ chords that bring that in this case, providing the melody with the rhythmic nudge along it needs. Still, a downbeat melody remains a downbeat melody, but Dylan compensates somewhat by singing continuously through the bar. It’s a bit like the trick that singers in French use: the language has no inbuilt rhythm or stresses, so they make up for that flatness by singing a lot, and if necessary, singing quickly. And as everyone knows, more notes = more energy. Which is what Dylan does here.

In the second part of the verse, on lines like “Didn’t you”, “kidding you” etc., he does what most of us would do in a verse, and holds the singing back till later in the bar, in this case, beat 3. It’s a contrast with the first 2 bars of the verse, and in holding it back, he leaves us dangling a little, which creates the kind of tension that helps move a song along. Still, it’s more of a comment, an exclamation mark on the first part of the verse, which is where the bulk of the lyrics are. This is reflected in the lyrics themselves, which become just a question in response to the statements of bars 1 and 2. The overall characteristic of the verse is in that downbeat attack for the beginning of the main melodic lines, carried through the first 2 bars of each verse and emphasised by the on-beat chord changes on one and three.

Subsequently, we get to the bridge, and Bob starts to really get to work in weaving his magic. For starters, he shifts the melody much later, to start the phrase on beat three for the “You used to”. It’s like he’s hit the brakes, and the melody is pulled right back in contrast to the downbeat start in the verses. This held-backness continues across bars 1-4 of the bridge, where the vocal entry oscillates between beat 3 and beat 2. But then from bar 5 he does two things. Firstly, he starts moving the melody forward, so it enters on beat 2 on “Now you don’t”. Secondly, he doubles up the changes, and for the first time in the song, we have a sequence of one bar melodic phrases. This after the verse which is blocks of 4 bar phrases, and the first part of the bridge which is in blocks of 2 bar phrases. These one-bar phrases start on beat 2, which once again mirror Al Kooper’s off-beat changes in the verse. Dylan subsequently moves the melody earlier yet again, until he gets us back to where we started in the verse, the downbeat, for the last 4 bars of the bridge. This happens on the words “ About having to be scrounging” and “ And say do you want to, make a deal”.

The effect of all this movement and displacement of the melody can perhaps be imagined in horse-riding terms, though it’s been a very long time since I’ve been on a horse. The verse is a gentle canter, with everything under control, but moving along. However, when we hit the bridge, Dylan pulls right back on the reins, holding the horse in check. But gradually, gradually, over the next 12 bars, he loosens his grip, letting more and more rein slip through his hands. The horse then starts to take off and accelerate, though still pulling against the reins all the time, until we finally hit the chorus, when it is unleashed.

And here we are off, boy are we off. Forget about starting the singing 2 or 3 beats behind the beat, or even as in the verse, on the beat. Bob is way way out in front: “How does it feel” starts a full, majestic, get-up-out-of-your-chairs 2 beats BEFORE the downbeat. Even the “Feel” is pushed an eighth earlier than the downbeat, the only place in the song where any of the key melodic elements don’t start on a beat. The melody leads the whole band, soars above the backing and drives the song. It’s incredibly “up” after what has come before in the verse and chorus, and accordingly, the song really lifts and takes flight.

This change in the temporal placement of the melody in the chorus is also remarkable in terms of how this shift shapes how we read the vocal, and thus, the lyrics. In the verses, where the words come on or after the downbeat and thus after the chord changes, the band leads and we have the feeling that the singer is responding, that he’s commenting and observing, listening and reflecting. Things pick up in the bridge where from a long way behind the band, he gradually starts to catch up. We sense that he’s becoming more animated, that what he has to say is more important, and that he’s building. The culmination of this is in the 4 bars before the chorus, where the singing becomes less regular, more syncopated, on lines like “You’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal.”

But then we get the chorus, where in terms of timing, he’s way way out in front, leading a band who we feel are almost struggling to keep up. Not only does he start ahead of the band and the chord changes, but he sings right across the beat, almost ignoring it altogether, as if what he’s saying is too important, too big, too powerful to be contained or constrained by a regular rhythmic pattern or structure. THIS is what I’m saying, THIS is what I’m talking about, THIS is what I want to ask you …. “How Does It Feel?”. One of the greatest lines in rock music, spat out with venom and mockery.

It’s not an accident that it comes across like that. This isn’t just a great performance, pulled out on the day of the recording. It’s built in to the writing and construction of the song itself, all set up by the 24 bars that come before it. 24 bars of, deliberate, meticulous work, ebbing and froing, but quietly building to the climax that is the chorus.

This isn’t the only great example of the craft of songwriting. It isn’t even the only example of great craftsmanship from Dylan himself. But there aren’t many songs that I can think of where on the back of inspired choices and great ideas, you have this level of sophistication in the way the harmonic and melodic elements are worked in terms of the form. At each moment, he has the harmonic tension and the corresponding melody where he needs it to be in terms of the unfolding of the story. At each moment he has us where he needs us to be, in terms of our relationship with the singing and the singer. I’ve listened to this song over and over for thirty+ years now. And I never stop marvelling, and I never stop getting pulled in and hauled along, even though I know exactly what’s happening. Last word to Bruce Springsteen on Dylan in general, but pertinent to this song in particular:

“He had the vision and talent to make a pop song so that it contained the whole world. ”

If you want a take a listen:

This is the live version from the original 1966 Don’t Look Back film from Royal Albert Hall concert. It’s from when he toured electric for the first time, with the musicians who would go on to to become The Band. This is the famous performance when someone in the crowd called out “Judas”, to which Dylan turned to the musicians on stage and said “Play it fucking loud”. Quality is a bit suss, but you get the picture.

The original studio recording is here:

Meanwhile, Bob, back in Perth in 1978, with his black and white Strat? If anyone’s interested in the set list from that tour, you’ll find it below. The Greatest Song Of All Time is slipped in at song 10. And looking at that list, it comes back to me now. He closed with Forever Young. I thought I’d forgotten almost everything about the songs they played that night … but not that.

The set list from hell:

1. My Back Pages

2. She’s Love Crazy (Tampa Red)

3. Mr. Tambourine Man

4. Shelter From The Storm

5. It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue

6. Tangled Up In Blue

7. Ballad Of A Thin Man

8. Maggie’s Farm

9. I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)

10.Like A Rolling Stone

11. I Shall Be Released

12. Señor (Tales Of Yankee Power)

—

13. The Times They Are A-Changin’

14. Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35

15. It Ain’t Me, Babe

16. Am I Your Stepchild?

17. One More Cup Of Coffee (Valley Below)

18. Blowin’ In The Wind

19. Girl From The North Country

20. Where Are You Tonight? (Journey Through Dark Heat)

21. Masters Of War

22. Just Like A Woman

23. To Ramona

24. All Along The Watchtower

25. All I Really Want To Do

26. It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)

27. Forever Young

—

28. Changing Of The Guards

29. I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight

© Peter Crosbie 2016. All rights reserved.

2 thoughts on “Analysis: Bob Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone””